Cycling in India

Mumbai on Two Wheels: Cycling, Urban Space and Sustainable Mobility

Mumbai is not commonly seen as a bike-friendly city because of its dense traffic and the absence of bicycle lanes. Yet the city supports rapidly expanding and eclectic bicycle communities. Arguing that planning professionals and advocates need to pay closer attention to ordinary people who cycle for transportation or for work, or who choose to cycle for recreation, Mumbai on Two Wheels offers an alternative to the thinking that dominates mainstream sustainable transportation discussions. The book’s insights come from bicycle activists, commuters, food delivery workers, event organizers, planners, technicians, shop owners and architects. Readers will come away with a new perspective on what makes a city bicycle friendly and an awareness that lessons for more equitable and sustainable urban future can be found in surprising places.

There are few things more humiliating than slowly walking a bicycle up a hill while the person you are supposed to be cycling with waits at the top. This is what happened one morning in July, 2015 during a ride in Gorai, a neighborhood on the outer edge of Mumbai…

There has been a resurgence of recreational cycling in Mumbai, as elsewhere in India, since the early 2010s. A significant reason for the new popularity of cycling has to do with the immersion in the urban landscape that it offers; people are attracted by the pleasures of the embodied experiences of cycling as well as inter- actions with the varied communities of cyclists with whom they share the road. This paper shows how surfaces matter both materially and metaphorically in opening new possibilities for understanding fun, recreation and pleasure. Whereas in critical urban studies and related fields, surface often connotes superficiality or a cover over the real, I argue that attention to surfaces and its pleasures is what enables people to emphasise the productive possibilities of ‘convivial alliances’ across differences and to promote an agenda for sustainable transportation politics that goes beyond infrastructure building.

What makes certain forms of transportation possible, convenient, safe or enjoyable is not only the planned infrastructure but also the organic urban form that has evolved over the centuries: the physical arrangement of homes, markets, and institutions, the way people interact as a crowd and unspoken expectations regarding how streets are used…

Cycling with Meera Velankar and Sheetal Bambulkar is a humbling experience. I discovered this on the Eastern Express Highway in Mumbai one Sunday morning as they cooled down after riding 80 km as part of their training for a 200 km endurance ride –called brevet – on a tandem bicycle. Other Indian women have done brevets, but not on a tandem bike….

A Sikh cyclist’s claim that mandatory helmet rules impinge on the constitutional right to freedom of religious expression has thrust the niche sport of endurance cycling into the centre of a Supreme Court controversy.

In July, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Delhi resident Jagdeep Singh Puri’s plea that the government create guidelines to prevent violations of religious freedoms by private entities. Puri initiated this case with the help of United Sikhs, an international non-governmental organisation, after he was prevented from participating in an endurance ride in August 2015 because he refused to take off his turban and wear a helmet.

Doctoral Education Reform

Partnerships between universities and community colleges are commonly perceived as a one-way street where the former extends expertise or resources to the latter. But that approach overlooks the growing interest in and potential for university–community college partnerships that draw from the experiences, skills and perspectives that both types of institutions have to offer.

We saw this potential after organizing an Institute for Reading and Writing Pedagogy at Brandeis University, which brought together eight Brandeis Ph.D. students and eight Middlesex Community College faculty members. Developed by the Modern Language Association, the institute pairs universities with community colleges for a week of intensive training in pedagogy. We expected a week of productive conversations and workshops on that topic, but what occurred went beyond our expectations.

[Published in Inside Higher Ed, November 23, 2023

ENABLING COMMUNITY-ENGAGED AND PUBLIC-FACING PHDS

By Jonathan Shapiro Anjaria and Moriah King

[excerpt] …The answers we offer show how we have been trying to figure out, together, a new vision of a PhD as we navigate our coinciding career transitions. This would be a vision for the PhD that values students’ previous experiences and encourages research that is collaborative and responsive to communities’ needs, and that leads to research outputs in languages and formats that are meaningful to people outside the academy.

Threatened with extinction, the recreational cyclist has returned to India. Bicycle sales are booming, cycling events more frequent and cycling clubs buzz with excitement. In the Mumbai metropolitan region, for instance, there are active cyclist groups in nearly every neighbourhood, from posh Bandra to the more humble Kalyan. These new riders are passionate: 5.30 am rides through the city can easily attract two dozen people.

What is the significance of all this?

Street vending and public space

Street food vendors are considered both a symbol and a scourge of Mumbai: cheap roadside snacks are enjoyed by all but the people who make them dance on a razor's edge of legality. While neighborhood associations want the vendors off cluttered sidewalks, many Mumbaikers appreciate the convenient bargains they offer. In The Slow Boil author Jonathan Shapiro Anjaria studies these vendors’ livesa nd stresses to illustrate how the struggle for space creates generative relationships among diverse parties. Pushing past the rhetoric that paints these people as either oppressed subalterns or inventive postmoderns, Anjaria advocates acknowledging the mingling of diverse political, economic, historic and symbolic processes on their own terms.

[This is the publisher’s blurb from the back of the book]

The Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Bill, 2014, was finally passed by the Rajya Sabha on February 19 and received presidential assent last week. This is to be lauded. Since the late 19th century, the official view has been to treat street vending as a problem, a nuisance, a backward practice that has no place in a modern city. The result has been a century and a half of skirmishes between hawkers and the authorities. This conflict is one we all know well: in most Indian metropolises, street vendors fleeing with bundles of vegetables in advance of the arrival of anti-encroachment trucks are common scenes.

Tucked in a forgotten space beneath a densely trafficked overpass connecting eastern Mumbai with the city’s more affluent northwestern suburbs is a godown, or warehouse, of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC). On most days, a small group of hawkers can be seen standing in front of this dreary gray structure, having come to retrieve goods confiscated from them during one of the municipality’s sporadic efforts to decongest the city. These traders are rarely able to pay the required Rs 1,200 fine to retrieve their goods,1 and the BMC staff have little desire to keep hold of the iron griddles, weighing scales, and display tables typical of Mumbai street markets. So, after a lengthy negotiation, the hawkers’ property is usually released for a lesser, unofficial and unrecorded, amount. At times, this negotiation is verbal, but at other times, it is conveyed through the hawkers’ act of standing in front of the warehouse office, leveraging the nuisance their presence creates for a lower payment...

On the quiet residential street in front of the apartment where I stay in northwest Mumbai, the day begins with a woman selling tea next to her husband, an occasional banana vendor. Their grandchild plays on a scooter while his father washes his autorickshaw. By the late afternoon, a cigarette and paan vendor appears across the road. Around the corner, a vendor toasts sandwiches opposite a man selling nimbus and leafy green vegetables from a small pushcart. A raddiwala cycles by, collecting old newspapers. An itinerant barber, his equipment stored in a small briefcase, sits in the shade of a shoe repairman’s roadside stall. A block away, a cluster of women sell vegetables perched against a fence, a man fries pakodas from a small metal stand, others pre- pare chaat and vada pao. Beneath an old tree, magazines are displayed next to two young men repairing tires, stacks of which are used to support a table for their neighbours’ food preparation.

How are we to interpret these street scenes?

Can researchers study fun and pleasure?

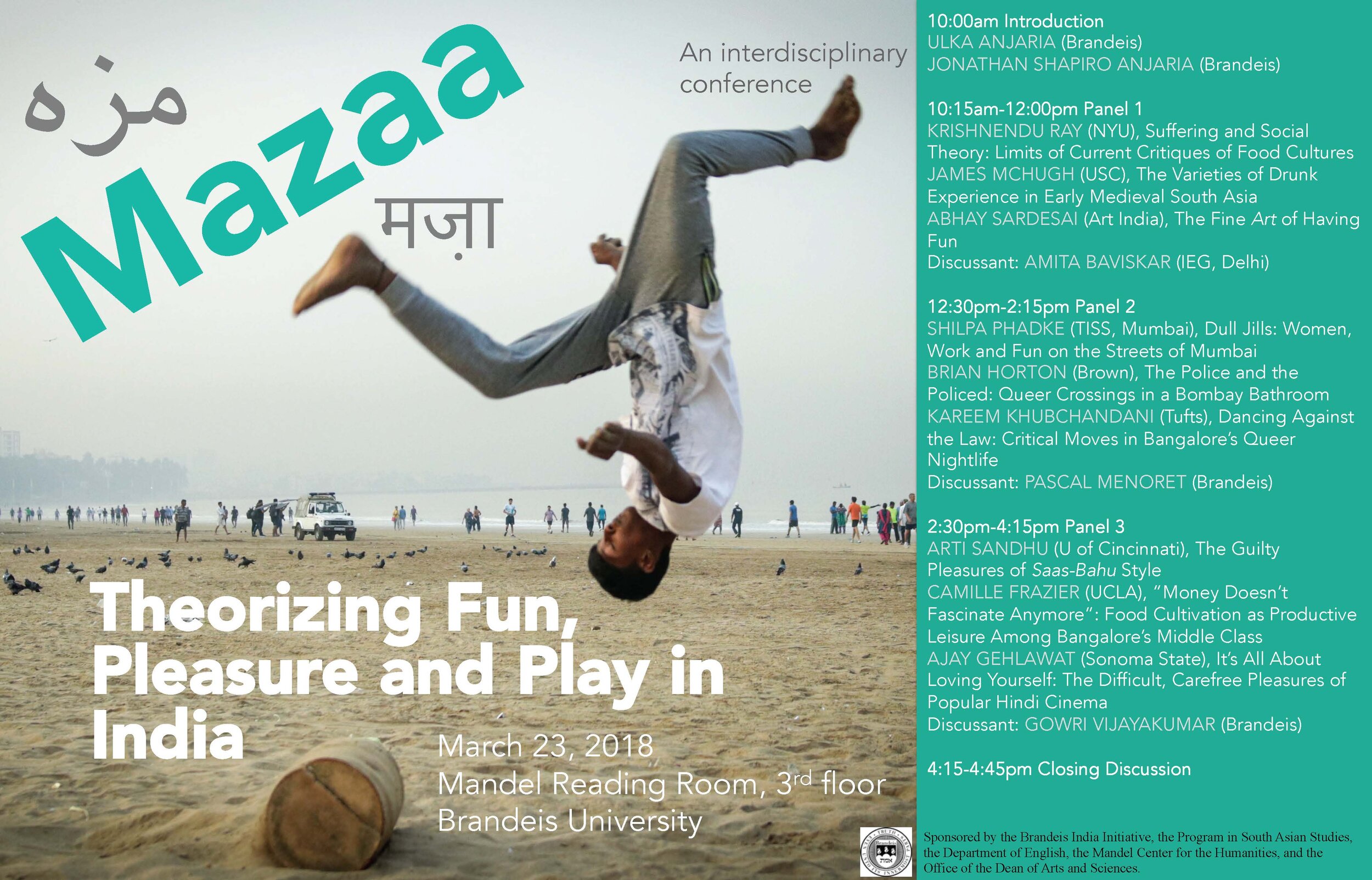

This collaborative project started with a conference organized with Ulka Anjaria at Brandeis in March, 2018 called Mazaa: Rethinking, Fun, pleasure and play in India. We edited a collection of essays published in 2020 which brought together writings on topics including food, sexuality, gender and public space, fashion and sports.

Scholarly writing often treats fun and pleasure as either frivolous, and therefore irrelevant, or as symbols of a more important social phenomenon. At times, this is motivated by political critique; researchers often believe that entertainment necessarily supports the status quo. At other times, researchers avoid mazaa because we are skeptical of things that have an embodied pull on us. Indeed, mazaa is sensuous; it draws us in with its viscerality. Rather than see these qualities as obstacles, we argue that mazaa’s embodied, unwieldly and seductive properties can generate new ways of knowing, analyzing, critiquing and writing. Dwelling in mazaa does not mean ignoring inequalities, violence or power, but finding new ways of writing about the forms of life that thrive even in times of crisis. It also means illuminating how pleasure can generate new communities and political possibilities as well as new understandings of the role of the critic in social analysis.